For the past month, AB InBev, parent company to the Budweiser and Bud Light beer brands, has been facing what many are calling a product boycott. [1] This situation started in early April when transgender social media influencer Dylan Mulvaney released March Madness-related, sponsored Instagram posts promoting Bud Light. These posts were immediately met by a wave of criticism within social media with many self-identified long-term Bud Light drinkers announcing they would no longer purchase the brand, with some encouraging others to join them. Within days, the news media was heavily covering the “Bud Light Boycott” story.

A sizable portion of this news coverage downplayed the likelihood of a significant monetary impact to AB InBev generally and Bud Light specifically. Citing conventional wisdom from public relations experts, they prognosticated that sales declines would be minimal, short-lived, and possibly more than offset by a counteracting buycott. [2] This has proven NOT to be the case.

Substantial Impact on Sales of Bud Light

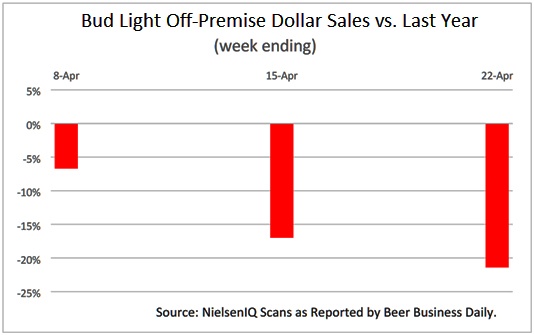

Sales for Bud Light fell substantially in the first week after the campaign. As weeks passed, declines intensified. By the third week, off-premise dollar sales versus a year ago dropped by over 21%. [3]

Competitor Molson Coors’ Miller Lite and Coors Light branded beers have been the primary beneficiaries of Bud Light’s decline. In the third week, Bud Light lost 8.3 share points in the domestic premium beer segment. Correspondingly, Coors Light gained 4.1 points and Miller Lite gained 3.7. This is almost a one-to-one transfer of market share from Bud Light to its two closest competitors.

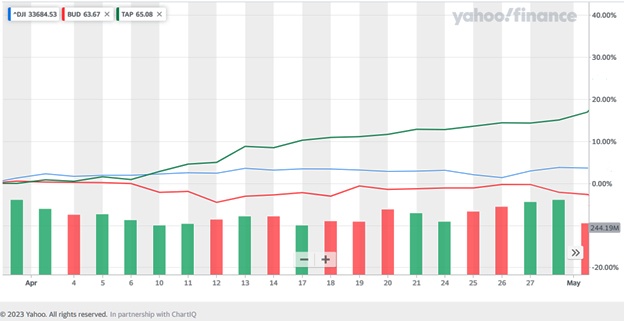

Investors may have taken note of these trends, with the AB InBev (ticker “BUD”) stock price falling and Molson Coors (ticker “TAP”) advancing, both in absolute terms and relative to the benchmark Dow Jones Industrial Average (ticker “DJI”). In absolute terms, AB InBev was down 3.1% while Molson Coors was up 17% in the month since the campaign broke, while the benchmark was up 2.3%. [4]

This corresponds to an approximately $4.3 billion drop in AB InBev market capitalization in absolute terms and $7.5 billion relative to the benchmark. If sales for Bud Light remain at these new lower levels into the future, this drop could be on the low end of realized brand value lost.

Why Is This “Boycott” Different?

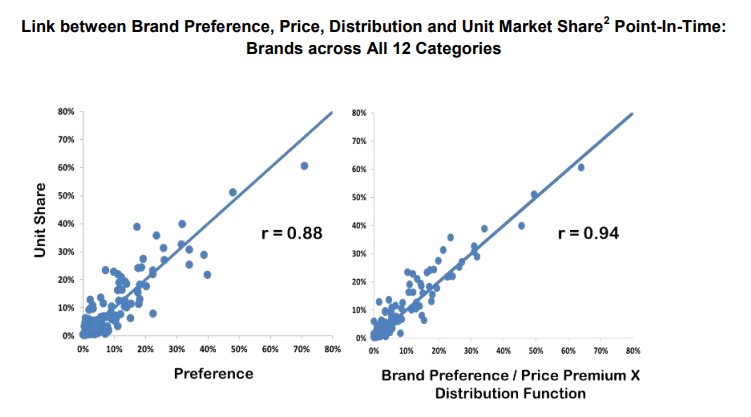

At the Marketing Accountability Standards Board, we see this situation as something other than a traditional boycott, and the reason has its roots in MASB’s landmark Brand Investment & Valuation study (March 2016). [5] MASB concluded that brand preference explains unit share variation to a much greater degree than other common measures such as awareness (both aided and unaided) and purchase intent. This two-year initiative spanned 120 brands across twelve diverse product/service categories, including alcoholic beverages.

Brand preference (or choice) represents which branded product is preferred under specific conditions of price and availability. Measures of brand preference attempt to quantify the impact of marketing activities in the hearts and minds of consumers and potential consumers. [6] Across all brands and categories within the study, brand preference accounted for 77% of the variance (r = 0.88) in unit share. The remaining variance was explained primarily by price relative to the competition and distribution. In some categories, brand preference played an even greater role.

To further close the loop – and this should be of interest to CEOs and CFOs as well as CMOs – MASB then published a related white paper in May 2018 that posited the linkage of brand preference to enterprise cash flows and brand value. [7] A subsequent white paper in June 2021 [8] fully closed the loop by making the connection to enterprise value. (In the case of public companies, that’s stock price!) Collectively, the findings from these studies inform why the Bud Light situation could be quite different from a traditional brand boycott.

Traditional brand boycotts are typically started by third-party activist groups to sway the policies of a brand’s parent company. These groups will issue a list of demands to the parent company and then call on brand consumers to refrain from purchasing the brand until these demands are met. In this scenario, the brand consumers continue to prefer the brand. In fact, success in motivating the parent company to meet the demands relies on the belief that the consumers will quickly return to the brand once they are met. These campaigns tend to be short lived and have a minor impact on company financial performance. Either the demands are quickly met (in total or in part as negotiated with the third party) or the consumers tire of forgoing their preferred brand. In either case, purchasing of the preferred brand resumes after a brief period.

Two other factors contribute to the short-lived nature of traditional brand boycotts. First, it is often difficult for a third-party group to generate the awareness and motivation among brand consumers necessary to significantly impact sales. In these cases, the boycott just fades into obscurity. Even when a critical mass is met, it is often met with an opposing buycott. This is when an opposing organization encourages the purchasing of the brand’s products, thereby dulling the impact of the boycott.

It is these factors that support the conventional wisdom that brand boycotts are short lived and have little substantive effect on the parent company’s financial status. But while this conventional wisdom is frequently right, in the case of Bud Light it could very well be specifically wrong. There is a high probability that the Bud Light brand is not facing a traditional boycott.

The immediate consumer response to Mulvaney’s posts was organic and spontaneous. There was no organizing third-party group. Rather it was an immediate groundswell of previous brand purchasers switching their preference away from Bud Light. A clear sign of this were text, image, and video posts on social media of these consumers, some famous but most not, disposing of the Bud Light they had on hand and communicating that they will no longer purchase Bud Light and other AB InBev products. There is no list of demands to be met for “still-preferrers” to begin purchasing again as in a traditional boycott. Rather, there were clear statements that consumers had permanently switched their preference to other brands of beer.

Remarks by Anheuser-Busch CEO Brendan Whitworth that “we never intended to be part of a discussion that divides people” [9] were viewed as inauthentic given heavily covered comments [10] by the brand’s Vice President of Marketing, Alissa Heinerscheid. An apparent attempted buycott by some prominent political figures only exacerbated the feelings of division. [11] Within a matter of weeks, ardent Bud Light drinkers were expressing sentiments of betrayal common in brand divorces – not boycotts.

There is no clear short-term fix to this branding challenge. It could take years of concerted marketing efforts for the Bud Light and other AB InBev brands to rebuild positive mental associations and regain lost brand preference. In its first quarter 2023 earnings call, AB InBev announced its intent to triple Bud Light’s marketing spending this summer. [12] The company is also changing its marketing focus to sports and music and will more aggressively screen their marketing creative. [13]

Meanwhile, the competition is seizing the opportunity offered by Bud Light’s troubles. In their first quarter 2023 earnings call, [14] Molson Coors CEO Gavin Hattersley announced strong summer marketing investment for Coors Light and Miller Lite. Of note in this emerging scenario, the last Super Bowl saw the return of Coors Light and Miller Lite to in-game national advertising after an absence of more than 30 years.

How can marketing leaders avoid a situation like this?

There are several things that marketers can do to stay out of a comparable situation:

1. Conduct brand-preference-based profiling before selecting brand spokespeople and influencers. The careful selection of brand spokespeople and influencers is critical. While it can be tempting to make choices based only on the potential reach to groups underserved by the brand, this can be a dangerous approach. From a brand safety perspective, it is important to measure how current fans of the brand perceive the spokesperson/influencer.

2. Do not be blindly enticed by the absolute number of followers for an influencer. A social media influencer’s absolute number of followers can include large numbers with negative sentiments about the influencer. Controversial influencers may have as many detractors following them as enthusiasts. For this reason, it can often be better to put together a portfolio of smaller non-controversial influencers than to concentrate efforts with a larger, controversial one. This portfolio approach is common in the newly emerging landscape of collegiate Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) marketing efforts and could be adapted to the management of other types of influencers. [15]

3. Actively review brand influencers’ posts prior to release. Many online channel promotions have been developed through a ready-fire-aim process whereby advertising is released and, if ineffective, yanked. In the context of larger, tested advertising campaigns, this is not risky as it is unlikely that preference-damaging creative will make it to production. But this is not an appropriate approach for social media campaigns where brand influencers produce the advertising content themselves. Social media algorithms encourage influencers to create material that is edgy to maximize clicks, views, and shares. It is therefore highly advised that brands screen influencer material prior to release to ensure it fits the brand’s image.

4. Do not expect accurate targeting to limit negative effects. There is a belief that online promotions can be so accurately targeted to specific audiences that reactions outside this group do not need to be considered. Research sponsored by MASB has shown that such targeting is not accurate enough for this, oftentimes being less than 50%. [16] How broadly promotions get distributed is now outside of the marketer’s control. Promotions can very easily be captured and reposted.

The Authors

Frank Findley is a data scientist serving as Executive Director of the Marketing Accountability Standards Board (MASB) where he represents the U.S. in the creation of international (ISO) marketing standards. His previous work at ARS group, comScore, and MSW Research resulted in improvements to ad testing, tracking, media planning, and competitive intelligence systems. He is co-inventor of the patented Outlook media planner. His research has appeared in numerous publications including the Journal of Advertising Research, Quirk’s, Forbes, and the books Accountable Marketing and Master of Marketing Measurement: Margaret Henderson Blair on Marketing Accountability. He was presented the 2021 ARF Great Minds Award for Best Practitioner Paper.

Frank Findley is a data scientist serving as Executive Director of the Marketing Accountability Standards Board (MASB) where he represents the U.S. in the creation of international (ISO) marketing standards. His previous work at ARS group, comScore, and MSW Research resulted in improvements to ad testing, tracking, media planning, and competitive intelligence systems. He is co-inventor of the patented Outlook media planner. His research has appeared in numerous publications including the Journal of Advertising Research, Quirk’s, Forbes, and the books Accountable Marketing and Master of Marketing Measurement: Margaret Henderson Blair on Marketing Accountability. He was presented the 2021 ARF Great Minds Award for Best Practitioner Paper.

Jim Meier served as MASB Director 2013-2018 and was appointed Trustee and Treasurer of the Marketing Accountability Foundation in 2019. After eight years as an auditor with Ernst & Young, he spent 26 years with Philip Morris, Miller Brewing Company and MillerCoors in financial support roles across Corporate Financial Services, Sales, Integrated Supply Chain, and Marketing. In his final role, VP Commercial Finance, he reported directly to the CFO and on a dotted-line basis to the CMO and CSO. He was closely involved with annual marketing spending allocation, on-going assessment of marketing mix modeling, and application of ROMI principles in both the Marketing and Sales divisions. Most recently, he has been engaged in assisting startup companies connected with a venture capital fund.

Jim Meier served as MASB Director 2013-2018 and was appointed Trustee and Treasurer of the Marketing Accountability Foundation in 2019. After eight years as an auditor with Ernst & Young, he spent 26 years with Philip Morris, Miller Brewing Company and MillerCoors in financial support roles across Corporate Financial Services, Sales, Integrated Supply Chain, and Marketing. In his final role, VP Commercial Finance, he reported directly to the CFO and on a dotted-line basis to the CMO and CSO. He was closely involved with annual marketing spending allocation, on-going assessment of marketing mix modeling, and application of ROMI principles in both the Marketing and Sales divisions. Most recently, he has been engaged in assisting startup companies connected with a venture capital fund.

References

[1] Source: Universal Marketing Dictionary, marketing-dictionary.org/b/boycott/.

[2] Source: Universal Marketing Dictionary, marketing-dictionary.org/b/buycott/.

[3] Bud Light Demand Continues to Deteriorate; Beer Business Daily, May 1, 2023.

[4] Source: Yahoo!finance in partnership with ChartIQ, finance.yahoo.com.

[5] Brand Investment and Valuation, a new empirically-based approach; MASB, March 2016.

[6] Source: Universal Marketing Dictionary, marketing-dictionary.org/b/brand-preference/.

[7] Applying the MASB Brand Investment & Valuation Model; MASB, May 2018.

[8] The Financial Value of Brands Imperative: Why Brands Must be Valued in Financial Terms; MASB, 2021.

[9] Anheuser-Busch Press Release; April 14, 2023, anheuser-busch.com/newsroom/our-responsibility-to-america.

[10] Bud Light’s marketing VP was inspired to update ‘fratty,’ ‘out of touch’ branding; New York Post, April 10, 2023.

[11] Photo of Democrats Drinking Bud Light Widely Mocked: ‘Beta Beer Party’; Newsweek, April 17, 2023.

[12] Bud Light boosts spending in US to counter sales declines; The Hill, May 4, 2023.

[13] Anheuser-Busch Changes Beer Marketing Focus After Transgender Promotion; The New York times, May 4, 2023.

[14] Q1 2023 Molson Coors Beverage company Earnings Conference Call: ir.molsoncoors.com/overview/default.aspx.

[15] Name, Image, Likeness and Influence – What Have We Learned from the First Year of College Athlete Sponsorship?; MASB Sponsorship Accountability Series, May 31, 2023.

[16] Digital Marketing Accountability: Targeting; MASB 2021 Fall Summit Presentation, November 11, 2021.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS ON OUR LINKED IN POST!